Looking at it today, with 50 years in his rearview mirror, he’s likely to share that he’s had the winning ticket all along. It certainly fits the narrative, given that he was named after a racehorse that his father, a jockey, once rode to victory.

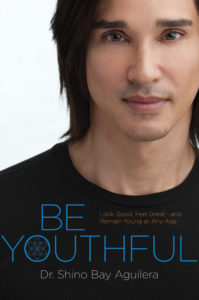

And on the surface, which is where physician Shino Bay Aguilera happens to do some of his most acclaimed work, there’s ample evidence to support such a contention. Patients at Shino Bay Cosmetic Dermatology & Laser Institute often speak of its founder as if he were part-magician, part-Buddha, an internationally renowned industry expert and sought-after speaker whose artistry with lasers and injectable techniques is matched by a Zen-like warmth and heartfelt affection for those he treats.

Social media reviewers rave at his ability to “stop the clock” on aging while in the same breath describing him as “genuine,” “compassionate” and a “beautiful soul.” One woman, still reeling from the death of her husband and suddenly raising four young children as a single mom, traveled from Naples to his chic, contemporary facility in downtown Fort Lauderdale to reverse the aesthetic toll that the past few years had taken on her. “Making the decision to seek you out has truly changed my life,” she wrote.

In that sense, the present represents so much of what Aguilera envisioned as a young boy growing up in Panama. As far back as age 5, he knew he was going to pursue medicine; if he wasn’t playing doctor or tinkering with chemicals as a kid, he was dissecting frogs in the backyard. In the bigger picture, he always saw himself as the kind of old-fashioned practitioner whose patients would become like family.

“I wanted to be the kind of doctor who could help people physically and emotionally,” he says. “When this branch of medicine opened, I knew this was my area of practice.

“For me, this is important. I take it personally. I invest myself. This is my life, my calling, my passion, my destiny. … It’s more than just fillers and Botox—I have to be on the journey with [his patients]. And they feel that.”

What his patients, peers, co-workers and industry admirers can’t feel—what no one except him can possibly understand—is everything he overcame to reach this moment. What he survived to claim his childhood dream.

By his own painfully candid admission, his are the kinds of scars that never truly heal. Even the most cutting-edge laser technology can’t mask them, not completely. But without the scars, Aguilera confesses, he wouldn’t be who he is today.

Innocence Lost

As Aguilera describes it, his father impregnated his mother just as she was about to turn 17. He was 18. “My grandma chased him with a broomstick until he married my mom,” he says with a smile. The union didn’t last. When Aguilera’s father learned of an opportunity to ride racehorses in California, he left Panama for good.

Father and son would reconnect at a pivotal moment in Aguilera’s life. In the meantime, his mother quickly remarried. “Back then, it was important for men in the culture to believe they were marrying a virgin,” Aguilera says. “So, I was treated like I didn’t exist for the sake of my stepfather’s honor.”

For much of his early childhood, Aguilera was raised by his grandmother, an immigrant in Panama without papers, without a husband (who had left her)—and with eight children of her own, as well as two other grandchildren.

“She did what she had to do to raise us because she couldn’t work legally,” Aguilera says. “So, she worked as a prostitute.”

Before long, the local children heard tales about his grandmother’s evening vocation. It marked a period of relentless bullying in his young life. “It’s one thing to be poor,” Aguilera says. “To be poor and to be raised by a prostitute, your status is less than zero.”

It didn’t help that, as a child, Aguilera was effeminate in nature and androgynous in appearance. When he wore his hair long, people couldn’t tell if he was a boy or a girl. In later years, he discovered that the bookstore next to his grandmother’s house tossed medical journals in its trash bin. In one such magazine, he read how being gay and androgynous was associated with diminished testosterone. So, he saved $40 to buy a month’s supply of a certain testosterone pill. “Being so poor, it took so long to save $40 that I only took it for that one month,” Aguilera says. “But maybe that’s why I’m so tall compared to my mom and dad.”

For the better part of three years, Aguilera endured routine attacks from a group of school kids. His uncle implored him to be a man and defend himself, or else he’d face similar consequences at home.

“So, every day I’d wait for these five kids to punch me, and I’d go home all beat up. It didn’t stop until one of them threw a rock at me and I started to bleed,” he says. “I think that scared them.”

Unfortunately, bullying wasn’t the only ongoing nightmare related to his appearance.

“I remember my life since I was 3 1/2, and I remember having sex since I was 3 1/2,” Aguilera says. “With many people. And, sometimes, many times in a day.”

Aguilera asked not to share the specifics of who sexually abused him except to say that it was men and women, relatives and neighbors—and all while his grandmother was gone at night. His grandmother would never learn about what transpired inside her house.

“Everyone wanted to have sex with me,” he says. “I thought it was because I looked a certain way. Maybe I caused them to have these feelings.”

He pauses as tears fill his eyes.

“I hated the way I looked.”

Rising from the Depths

Rising from the Depths

It wasn’t until his first communion, upon learning about sin, that Aguilera realized there was nothing ordinary about his day-to-day existence.

He blamed himself for what was happening. So, at age 9, he attempted suicide.

“There was a little girl [from his neighborhood] who killed herself by drinking DDT, the pesticide for mosquitoes. I thought that would be the easiest way,” he says. “I didn’t want to jump in front of a car. I just wanted to fall asleep. … But I didn’t die. I woke up in a hospital; I was wearing diapers, and my hands and feet were tied to the bed. It was so humiliating.”

It also led to an epiphany. He didn’t need to kill himself. He just couldn’t stay with his grandmother. Aguilera moved from house to house, living with different family and friends—and still, from time to time, enduring episodes of sexual abuse. His escape, he says, was in his mind. He created a fantasy world with an imaginary family “that was just like the family on [the late 1970s TV series] ‘Eight is Enough.’ In my head, I would take myself somewhere else—but it was always in the United States.”

As he reached his teenage years, Aguilera struggled with the anger that was simmering deep within. He wanted people to pay for the pain they had caused him. But, for the first time, he also saw a flicker of light at the end of his tunnel. He found a high school near where his mother and stepfather lived, an American institute that challenged his incisive and curious mind.

For several years, in order to have a base near the high school, his mother allowed him to sneak into her house late at night and sleep in the laundry room, so that his stepfather wouldn’t know he was there. Compared to some of the places he had lived, the laundry room was like “the Taj Mahal,” he says. More important, it was a means to a better end. He had to finish high school. And he had to suppress the past.

“Something told me that if I kept on that path of anger that none of my dreams would come true,” he says. “So, I decided to stay in the light. I didn’t want to hate people and have that poison in me.”

At age 17, he won a contest sponsored by the local Soroptimist Club—Best Young Citizen in Panama. Incredibly, Aguilera’s father, who was living in Orange County, California, read a newspaper story detailing his son’s achievement. His father petitioned for him to come to the United States.

Aguilera would work different jobs—dishwasher, bank teller and, most notably, as a successful male model—to pay for school at Pasadena City College and the University of California at Los Angeles, where he earned his Bachelor of Science degree. He graduated from Western University of Health Sciences in Pomona, California, as a doctor of osteopathic medicine in 1999.

An internship-turned-residency (in 2000) at Wellington Regional Medical Center brought him to South Florida, where he’s been ever since.

“I was marked in Panama. Here, in the United States, I could reinvent myself,” he says. “Nobody knew about my past. This was my rebirth.”

Asked if he ever sought therapy to deal with the years of abuse, Aguilera shakes his head.

“I never felt alone. There’s an inner voice that guides me and counsels me,” he says. “It’s probably the same voice I hear when I meditate. … Therapy isn’t going to give me tools to make me feel better. And I needed to feel it. I needed to feel weird, different, unattractive, gay … I’ve felt all the labels. And it’s helped me to be the best doctor, to relate to patients and to make a difference in their lives.

“I know that I was damaged. But I needed to be damaged to be exactly where I am now. My success allows me to get better and help other people get better.”

Finding Perspective

As the story goes, Aguilera was already a board-certified family practitioner and lecturing about laser treatments when the dermatologist normally used for presentations by his ex-boyfriend, Richard Goren, who worked as a representative for a laser company, cancelled on the day of a scheduled lecture. Aguilera, who used to sign people in at these events and knew the presentation like the back of his hand, offered to step in.

“I had never spoken in front of a group like that before—and I have this very thick accent,” he says. “So, I was freaking out a little bit. But I had to help [his ex], because he was about to have a heart attack. Well, we sold five [skin rejuvenation] laser machines that day. At the time, they cost around $100,000 to $150,000.

“From there, it was like, ‘Every time Shino lectures, something gets sold.’ That was [Goren’s] job. My job was to educate, which I loved to do. I ended up speaking about that technology for 17 years.”

Along the way, he and Goren put together a business plan that combined elements of a traditional dermatology practice with the burgeoning and cutting-edge laser technology to which they had access, leading to the opening of the state-of-the-art facility on Las Olas Boulevard in 2007. Today, Aguilera and Goren are still business partners and good friends—and the practice is the officially certified “Laser Center of Excellence” and U.S./Latin American physician training center for Cynosure, a leading laser manufacturer.

As the cosmetic dermatology industry has grown, so has Aguilera’s areas of expertise. Shino Bay Cosmetic Dermatology is the top volume injector in the United States of Sculptra, the wildly popular poly-L-lactic acid dermal filler for which Aguilera also serves as the preeminent physician trainer.

“He can stand on stages all over the world, the biggest stages in his industry, and have top doctors and plastic surgeons come listen to him,” says Loren Psaltis, director of business development at Shino Bay. “But I get bothered sometimes because I fear he has this Michael Jackson/Whitney Houston complex. You’re the most beloved person in the world, and you still don’t feel it. …

“When the best in the world invite you, and the room is dead quiet—standing room only—this is the magic of this man. The talent is real. … Beyond his back story, which can move mountains, it’s who he is now. It’s his place in the industry. That’s tangible. And it’s American.

“If his journey isn’t the American Dream, I don’t know what is.”

Professionally speaking, as he passes the half-century mark, Aguilera clearly sees that journey in more profound terms. He stopped taking on new patients over a year ago, in part because he wants to speak more about the holistic side of his industry.

“I’m more secure now. I speak my mind more, instead of swallowing my words,” he says. “There are things I want to share, more spiritual things. This is my duality, keeping people younger but also making them feel OK about the aging process. … I’ve been feeling that I have a bigger, more important message to share with the world.”

Personally speaking, Aguilera found love, marrying his partner Alejandro two years ago during separate ceremonies in Colombia and in Fort Lauderdale, the latter over which Psaltis presided. He’s also found peace, he says, thanks in part to an astrologer. She explained to him that he was a very old soul, an ascending Scorpio. That no old soul comes into this world without having a difficult childhood. And that the reward is a happier adulthood.

As an old soul, the astrologer said, the universe gives you an assignment that you’re strong enough to handle.

“Everything bad that happened to me, it shaped me to be doing exactly what I’m doing right now,” he says. “I can help people because I have compassion. I understand. But, also, I have skills to help them love themselves.

“I think that’s why I enjoy doing what I do. I know what it’s like to dislike the way you look. Even when there’s nothing wrong with you.”