How does fiction happen? Sometimes it’s the product of two or more real-life people or circumstances that have nothing to do with each other; then the author connects them or makes them collide to see what will happen. Jane Smiley did this in her acclaimed short story, “Lily”: She took three friends of hers—a single poet and a married couple—who didn’t know each other, and mashed them together to see what trouble would ensue.

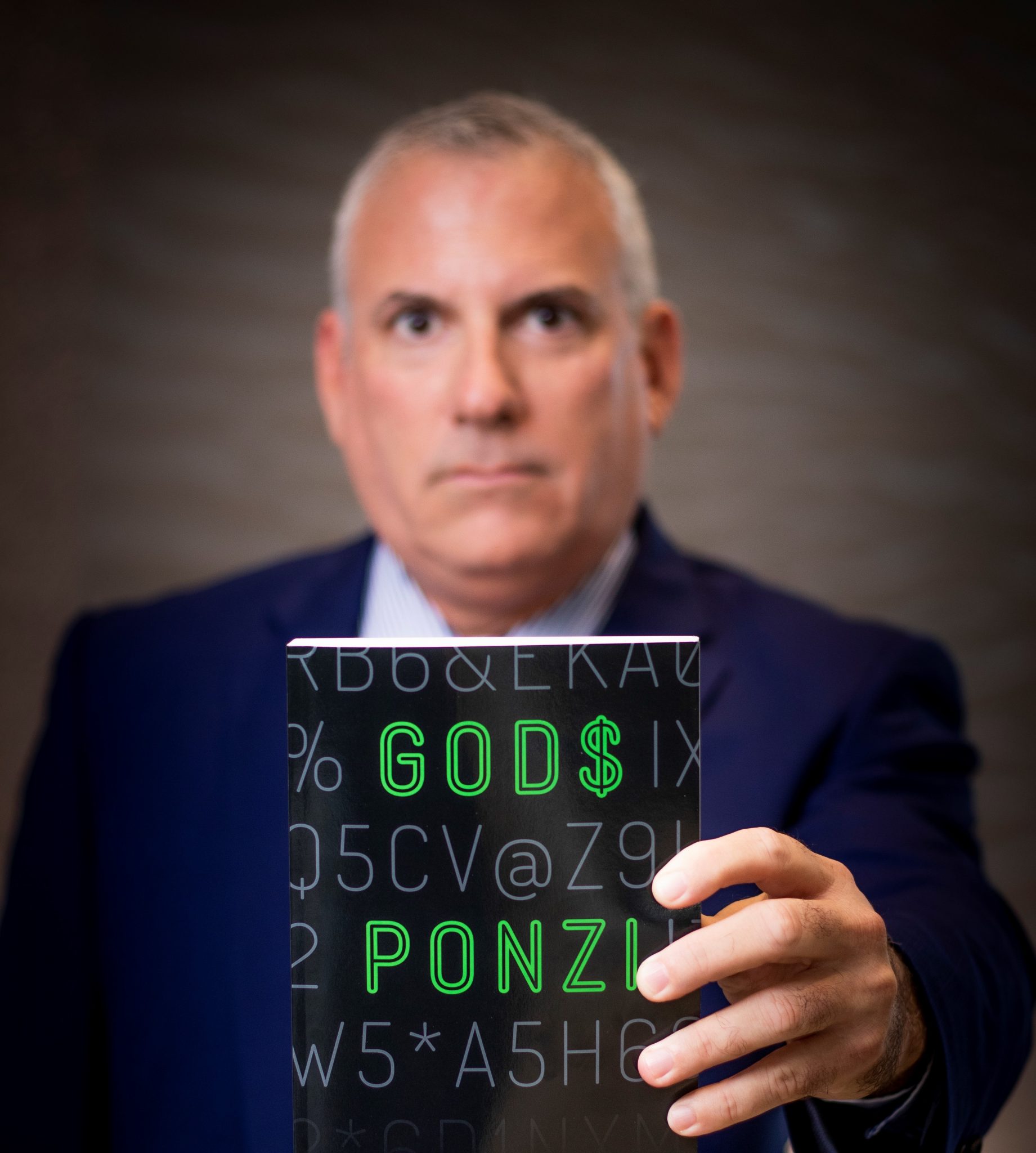

In God’s Ponzi, attorney and author Robert Buschel also made use of two disparate situations and drew them together. The first was a scam conjured by a Bernie Madoff-type character with discernable echoes of Scott Rothstein, a South Florida lawyer who was sentenced to 50 years for his own $1.2 billion Ponzi scheme. (Buschel practiced law at Rothstein Rosenfeldt Adler, where Rothstein served as CEO.) The other was the tragic story of an idealistic MIT techie named Aaron Swartz.

At an SFBW CEO Connect event held at the year-old Kimpton Goodland Hotel on Fort Lauderdale Beach, Buschel signed books, answered questions and opened a window into his creative process as he described what drives his main character Gregory Portent to do what he does.

In order to keep the reader on his side, Buschel explained that he had to come up with a good reason to launch a Ponzi scheme—“good” being relative. “The reader has to say, ‘I accept the revenge. These lawyers deserve to be taken out,’” Buschel said. Then he described the real-life inspiration for this premise: “The person who died in the book is an almost true-to-life character who killed himself based upon being attacked by a bunch of lawyers. He was an MIT grad [Swartz] who helped start Reddit and Creative Commons. He believed that all information should be free—that was his philosophy.”

Swartz, infamously, took matters into his own hands: “He ended up going into the MIT server and downloading a ‘skillion’ documents and putting them out to the world,” Buschel recalled. He was arrested for wire fraud and 11 violations of the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act; at one point, Swartz was facing 50 years in prison and $1 million in fines. “The government indicted him for stealing documents that are otherwise public,” Buschel said, referring to millions of pages of federal court documents. At 26, Swartz hanged himself in his Brooklyn apartment. In death, he became a martyr, a hero, an icon of the internet age. “I thought, that kid deserves a Ponzi revenge,” Buschel said.

“Portent is doing his Ponzi scheme for revenge; he’s not doing it to make money,” Buschel stressed. “But even that is a hard thing to do, to keep a Ponzi scheme afloat, because as you know—or if you don’t know enough about Ponzi schemes—you need new investors to pay off the original investors. And when the new investors stop, you’re in trouble. I always wonder if there are Ponzi schemes that actually land, without anybody actually getting hurt. Does somebody go, ‘OK, I’m going to stop, I’m going to take in all these new investors, pay everybody off, and everything is going to be OK and we land softly’? I suppose we never hear about those.”