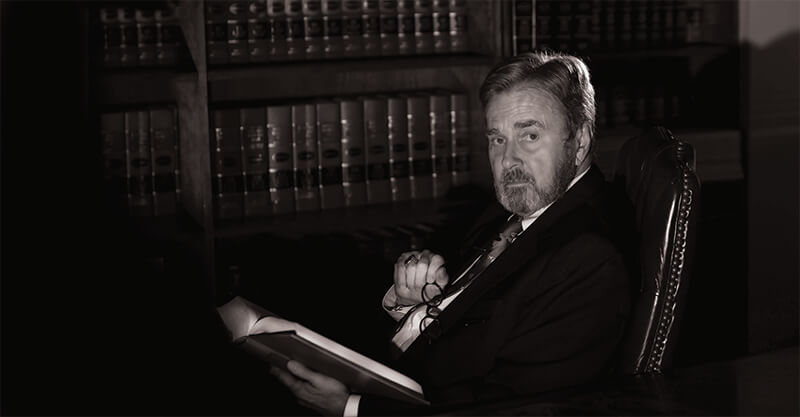

J. David Bogenschutz leads on the courtroom scene

By Andrea Richard

Being charged with a crime can ruin your life. Putting up a solid defense can help, if you are able to hire the right lawyer. That’s how J. David Bogenschutz has built his name as one of South Florida’s most prominent criminal defense lawyers.

The Fort Lauderdale-based lawyer has represented judges, law enforcers and politicians accused of misdeeds. That includes Jean Robb, who was accused of violating ethics laws as mayor of Deerfield Beach; three of the last six Broward County sheriffs, who were accused of crimes including corruption; and Miriam Oliphant, Broward County’s former supervisor of elections, who was removed from office by Gov. Jeb Bush in 2003 for malfeasance. He also represented former New York Yankees baseball player Jim Leyritz in a high-profile 2010 DUI manslaughter trial, in which Leyritz was convicted of a lesser charge and got probation.

With more than four decades of experience practicing law in South Florida, Bogenschutz, 73, knows the legal system but, more important, the region’s heavyweights and judges. It is his reputation that brings him business referrals, landing him enviable cases and keeping him busier than ever, he says.

Currently, he represents 20-year-old rapper XXXTentacion (given name: Jahseh Dwayne Onfroy), who is charged with domestic violence involving his pregnant ex-girlfriend. He also represents a physician assistant associated with the Rehabilitation Center at Hollywood Hills, where a dozen residents died following a power outage caused by Hurricane Irma.

Last year, he successfully defended Ronald Melnik, a deaf fitness trainer accused of murder, by arguing that the 2011 shooting was in self-defense. Also, after several years on the case, he got an acquittal in 2015 for Howard Skibinsky, who was charged with attempted murder after police said he cut his wife’s neck with a bread knife. And nearly 20 years ago, in a trial televised by Court TV, middle school teacher Beth Friedman walked without jail time after she was accused of having a sexual relationship with a 15-year-old student and was acquitted of five of six charges, thanks to Bogenschutz, who discredited the boy’s story. (She was convicted only of contributing to the delinquency of a minor, because the jury found she gave the boy drugs and alcohol. She served a year of probation but had faced 76 years in prison.)

“He doesn’t leave a stone unturned,” says Karen Laythe, his longtime legal assistant.

Originally from Xenia, Ohio, he got his start in a Dayton law firm as a summer intern in 1969. He worked on probate, real estate and domestic cases—divorce, adoptions. “Divorce? I didn’t like it. It was too difficult in terms of emotions, very acrimonious,” he says. “I felt like I wasn’t doing any good, that I wasn’t making a dent anyplace. I worked for Bobby Kennedy in 1968 in his campaign, so I was a wild-eye liberal like we all were in the ’60s.”

Eventually, he decided to leave the Midwest and move to South Florida, where he had visited during college spring break. He took a job in 1971 at the county solicitors office (which eventually morphed into the state attorney’s office) as a prosecutor in Fort Lauderdale.

“I would go into court and my calendar would read something like this: speeding in a posted zone, attempted rape, DUI with no driver’s license, murder in the second degree,” he recalls. “And the judge would say, ‘OK, are we going to try a case today?’ Yeah, judge, we are going to try the murder case, we’re not going to try the DUI. It was serendipitous as hell,” he says.

Then the county court became responsible only for misdemeanors, while the circuit court oversaw felonies up to first-degree murder. Back then, the state attorney’s office had only about three lawyers, he says, and all they handled were capital cases.

“We all became state attorneys three months later and we handled everything. I created what was the special investigations division that’s got 12 lawyers now,” he says. “They handle political corruption cases.”

Running that division laid the foundation for the young advocate’s law career. About a year later, he became chief of the trial division, where he handled all the trial lawyers and was able to pick the cases he wanted. “I was lucky. I got a lot of good cases,” he says.

In 1973 and 1974, he continued to polish his work. “My first lucky break was being able to practice law before Judges John Ferris and Dan Futch. They were two judges who were legendary over there,” he says. “John Ferris, he was called the conscience of the court of record. You got a real tough judge who is tough on you and you learn how to act like a lawyer. And you have a great judge who teaches you how to be a lawyer.”

Eventually, he became the chief administrative assistant. In 1976, he lost the race for state attorney against Michael Satz. Satz still holds that office and Bogenschutz went into private practice the following year.

“I’m an action junkie,” he says. “I had a kindred spirit for criminal law because it’s high stakes. It’s one thing to sit there and argue with a guy whether he’s going to collect $100,000 or $15,000—it’s another to stand next to a guy who is looking at going to prison for the rest of their life, who is at their lowest point in their life. The lowest point. You got the entire system of government coming down on their heads—judges, prosecutors, cops, agents, everybody. And they got one thing. They have a little thing called the Constitution.”

Today, he spends most of his time working on public corruption and white-collar cases, at the state and federal levels. For instance, in 2014, after 5½ years on the case that went on trial, he successfully defended former Deerfield Beach Mayor Al Capellini against corruption charges.

And in 2010, in one of the county’s biggest public corruption scandals during which father-son developers Bruce and Shawn Chait were charged with bribing politicians to move their golf course development project forward in Tamarac, Bogenschutz struck a deal. The Chaits pleaded guilty to unlawful compensation and received four years of probation in exchange for their cooperation in the state’s investigation. They were facing 35 years in prison. Numerous county officials were convicted.

“I told them [the state attorney’s office] that these guys can help you, but they aren’t going to help you if they go to jail,” he says. “After six months of going back and forth, we eventually cut the deal and everyone thought it was outrageous.”

Florida is notorious for its bizarre crimes that end up as salacious news headlines, but Bogenschutz says his practice doesn’t get quite so weird. “Bill O’Reilly once told me, when he was at Fox, that he subscribed to the Sun-Sentinel and the Miami Herald because the weird cases that would come out of here were like … I can’t even tell you how is that happening,” he says.

Bogenschutz doesn’t market his services; instead, he gets business mostly from referrals.

Clients come in with all sorts of ordeals. Having worked on both sides of the justice system, he knows what prosecutors are looking for, which helps to better defend and advise his clients.

“It depends on what the client wants to do. For instance, let’s say you come in and say, ‘I have just stolen $500,000 from my company and they found out about it and they are charging me, and I did it,’” he says. “My view of my job is, I say ‘OK.’ We are not going to do anything that lies about it. We are not going to stand up and say, ‘My client is absolutely innocent.’ But what we are going to do is make sure that if they want to convict you of this crime, they can prove it. That’s all. I’m not telling prosecutors that you’re guilty. I’m saying: Prove it. How are you going to prove it? Can you prove it? They must, or you’re going to walk. You don’t set the bar so low that anybody in their right mind accused of a crime could be convicted.”

Yet innocent people still go to jail.

“I would like to think and hope that it doesn’t happen often,” he says. “See, a lot of what we do in this business is not necessarily try to prove that a person is innocent. We don’t have to do that. The Constitution has already done that for us—you’re presumed innocent. Most jurors don’t like that, and they have a tough time understanding that, believe it or not.”

He says prosecutors will file charges as high as the facts allow, which presents more opportunity for the defense to break them down during negotiation.

“In a criminal case, you start out as a winner because you are presumed innocent,” he says. “They have to show by the evidence in the case that you are guilty. Period. All you have to show is a reasonable doubt—the slightest scintilla of evidence that gives you a reasonable doubt. You’re either guilty or not guilty.”

Bogenshutz says he isn’t there to assess an individual’s culpability. He’s there to preserve justice.

“It always fascinates me that you’ll get an individual who comes in and say, ‘I’m charged with XY and Z,’ ” he says, telling them “OK, well, this is what you are looking at. These are the guidelines. Tell me what happened. I want to know. Some lawyers say they don’t want to hear it. A lot of individuals will look at you and say, ‘If I tell you, you’re not going to fight hard for me, because you’ll think that I’m guilty.’ Well, if you don’t tell me, I’m not going to know where the arrows are coming from so I can dodge them.”

What matters is thoroughness, knowing every detail in the case so he can prepare for closing arguments in trial or negotiations when a client takes a plea or breaking down a charge, he says.

“It doesn’t matter to me—legally or professionally—if you are innocent or guilty. That’s not my job. My job is to make sure that no matter what happens, no matter what you did, that the state of Florida or the United States of America is not going to railroad you just because they can,” he says. “We lawyers, good lawyers, stand between our government and our clients.”♦