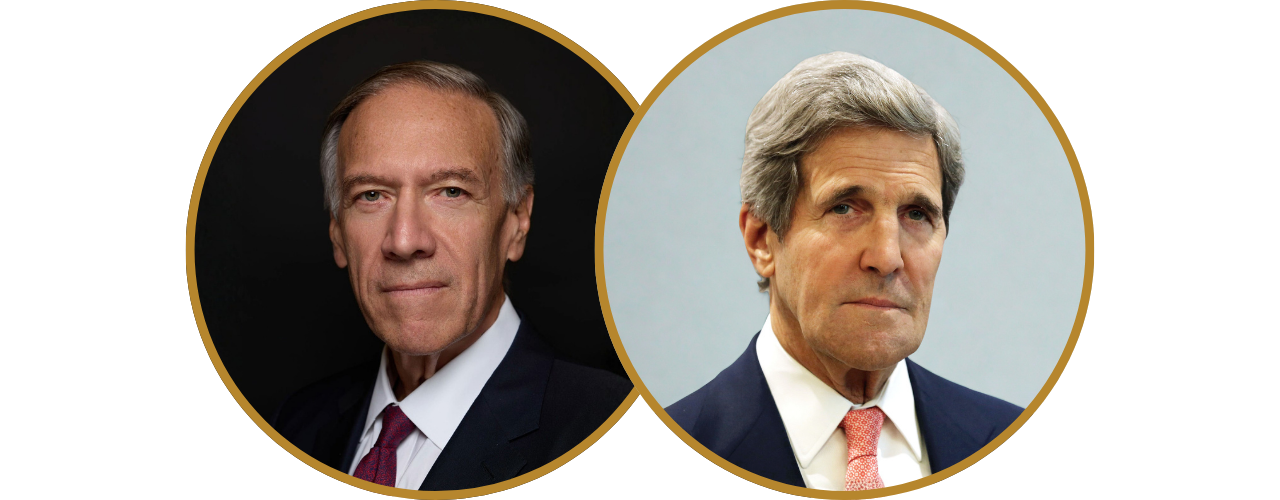

Bernardo Fort-Brescia and Arquitectonica have made a mark in Miami and around the globe

Arquitectonica is synonymous with Miami’s ranking as a global center of architecture, and Bernardo Fort-Brescia was on the ground floor as a founding principal of the firm.

The opening scenes of the original “Miami Vice” TV series have a glimpse of the Atlantis Condominium, one of the first buildings that put Arquitectonica on the map with its distinctive sky lobby, featuring a palm tree and bright red stairway.

After graduating from Princeton as an undergraduate and later going to Harvard to complete his masters in architecture, Fort-Brescia came to Miami in 1975 to teach at the University of Miami. In 1977, he founded Arquitectonica with a group of young architects that included his wife, Laurinda Spear.

It is one of the pioneers of globalization in the architecture profession, designing skyscrapers, opera houses, resorts and new cities.

Arquitectonica has more than 900 architects and projects in more than 60 countries around the world. It has offices in Coconut Grove, New York, Los Angeles, Lima, Sao Paolo, Paris, Dubai, Hong Kong, Shanghai and Manila.

SFBW talked with Fort-Brescia over lunch at Quinto La Huella, one of the restaurants at Brickell City Centre, which Arquitectonica designed.

The following transcript has been edited for brevity and clarity.

When did you first start discussing Brickell City Centre with Swire?

During the downturn, this land became available, and Swire called me up around 2010. They were cautious and wanted to know what density was possible and what was feasible. They eventually put it under contract and we started working on a scheme that eventually became what you see today: a mix of office, hotel, residential and retail—the Rockefeller Center of Miami—creating a new focal point for the Brickell neighborhood.

What was the initial concept like?

The concept was not to do a mall. If this were a classic mall like Dadeland, we would have closed the streets. It would have been a box outside. Instead, this has stores that open to the streets. The city grid is maintained as it was. It connects underground and above-ground.

This is the first time I have seen in the United States where there is a four-block development and there is no disruption of the historical bones of the city. The surrounding sidewalks are activated and made to come alive with shops and residential property, and the hotel opens to the street.

The other aspect of the concept is there wasn’t a single entrance. Usually a mall has one or two. On every block, there are two or three ways to enter. There are discreet passages like a city that has little alleys.

We created this promenade that threads through all these blocks. We thought it would be nice to leave it open with protection from the rain and direct sun.

Then, we went as far as to shape it to capture the breeze of the trade winds and cool off naturally. By virtue of the height, the southern and western lights are blocked by series of brise soleil. It’s called a climate ribbon from the fact that it creates a microclimate. It uses nature and the climate of our city to create a comfortable space. It also collects water that is used to irrigate all the gardens.

The word “ribbon” comes from the fact that we have four blocks and we have to connect the four blocks. This ribbon is the unifying piece that collects all these blocks and unifies them into one entity.

When you look down from the high-rises, the climate ribbon creates this gigantic piece of sculpture. It’s lit up at night. We have a 10-acre park on the roof of this podium, a green roof that can be looked at. It absorbs the heat instead of reflecting it. It creates a central park for the neighborhoods.

How did you and the developer work together to come up with a cohesive concept that would include so many different elements—office, retail, hotel and residential?

I have been working as an architect for Swire since 1993, when I was selected to do a large mixed-use retail and office at Kowloon Tong Station, where the train from China crossed the metropolitan train of Hong Kong. It has a huge bus terminal and taxi terminal. Festival Walk has 1.1 million square feet of shops and was our first major project in Asia. It was extremely successful.

Swire has had a vision of the future, including mass transit. Here, we are between Metrorail and Metromover. Swire wanted to integrate the people mover to encourage people to walk and bike. If someone used a car, they would go down into a basement. It’s the first major underground parking garage in Miami that linked all the blocks.

The offices, hotel and residential are all suspended over this garden. They don’t take space from the retail. The retail occupies the podium, and these objects are floating.

What can we expect as subsequent phases unfold?

We are already working on the next phase renderings with office, residential, hotel and three levels of retail. The climate ribbon will keep going and reach out to the corner of Eighth Street and Brickell Avenue.

Do you expect to be doing work in the historic area of downtown?

Yes, we have work there, but I can’t talk about it yet.

Arquitectonica also designed SLS Brickell.

Yes, it has restaurants, a hotel and residential also. It has four restaurants, a second-floor bar, a pool deck that is amazing, a big spa, a 137-room boutique hotel and 40 apartments on top in one building.

Tell us about your childhood and how you became interested in architecture.

I grew up in a place when I was a child that was like a park. By the time I was a teenager, a city was being built around it. Today there are skyscrapers, houses and hotels.

We had a dairy farm when I was a young child. Maybe seeing all this happen around me made me excited about construction and a place that was manmade. I was always interested in architecture, always sketching buildings.

What made you decide to go to Princeton and then Harvard?

Princeton had a famous undergraduate program in architecture. Harvard and Yale didn’t have it. I wanted to do a four-year program in architecture and urban planning. Then I went to get my masters in architecture at Harvard.

So, you initially taught at Harvard, but then came to the University of Miami. What made you decide UM was a good fit?

I had a good friend from Princeton, Andres Duany. He called me and said, “Why don’t you come down here and teach. Come for a year—you will like it and stay.”

I’d never lived in the tropics. Lima is always cold. I thought this is interesting, let’s look at a different culture.

On my last day in Cambridge, my roommate invited someone over from Miami, Laurinda, who was studying at MIT. She stayed one more year at the university.

What prompted you and your partners to start Arquitectonica?

Teaching was interesting, but I went into architecture school to build.

So, is it true that the name of your firm was just a placeholder?

Absolutely, we were panicking and registered how you say architecture in Spanish. Immediately, it got written up. We couldn’t change it. We were 26 years old and doing high-rises and were being written up everywhere.

I saw one interview that said your motto is “Never plan!”

I don’t say that. It was out of context. There is some degree of planning. But we didn’t go into this thinking the firm would be the size it is. We went into this because we are architects and love to do projects. We have a dream that every project is going to be fantastic. It starts with a sketch. You do your job with conviction and passion. You love what you do and things happen on their own.

At the beginning of the firm, there was no planning—it was just energy. But, eventually, we had some degree of planning. We never had a plan that a client would call us out of the blue from Hong Kong!

How do the dynamics of being partners in business and partners in life with Laurinda work?

Architects have difficult family life because we have to travel, have to prepare for presentations and have incredible schedules where you don’t sleep. If your wife is not in the same field, they will never understand it.

We have six children. Sometimes, we would bring the basket with the baby to the office and travel with the basket. We have been married for 40 years. Two of our children are architects who work with us, two are physicians, two are in New York working and studying—one is in law school and another is in real estate development.

One of your most famous early projects was the Atlantis. What inspired it?

The public remembers there is a hole and a palm tree. To us, it was more. It was a city that was changing. There was a house there that was rezoned by Mayor Maurice Ferré. He changed the zoning south of the Miami River bridge. It’s thanks to him that there is a Brickell Avenue. Atlantis was at that point where there was one house and there were going to be 100 houses.

We thought, “Well. What’s happing here? If you would have put a village there, it would have been horizontal. If you flip it on its side, it would be a vertical city.” So, we put in this big grid. Every three floors is a grid. In a traditional city, one of the main blocks is removed and it becomes a main square.

We shaped the tip of it on the bay side like a bullnose to give it a tropical shape. On the city side, we put that triangle on top as a symbol of the city. It was bridging city to bay. In a plaza in the traditional square, there is a monument and trees. There was no room for that but we put in a palm tree and a red stairway. Everything is functional. In this case, there is a pool in this space. So, you transform symbolism to functionality.

Then we have an aesthetic. We thought the whole city was turning beige and brown. We went the other way. We painted it electric blue and the stairway red and an interior wall was waving in yellow with the flair of the urban tropics. It’s more exuberant and more fun.

We were trying to redefine Miami and trying to say who we are and who we are not.

Very quickly, we were doing projects in San Francisco and New York. By 1984, we were doing major projects in South America. By 1988, we were doing major projects in Europe.

Eventually, in the early 1990s as Asia was awakening, we did projects in Hong Kong, Singapore and Manila. We were very bold and risk takers. We did it because I liked it. I love going to other places and meeting other people and cultures.

How has South Florida evolved as a center of notable architecture, whether it’s buildings, the architects who live here or the star architects who design projects here?

We have an advantage. We are a modern city. We only have a century of life, therefore everything is open. There is an opportunity to be creative. The city went from having the oldest average age of residents to the youngest. That brings energy and creativity that makes us a place where architectural innovation can thrive.

Today, we are a cosmopolitan place where Europe, the northeastern United States and Latin America meet and create an environment because there is an exchange of ideas. Star architects want to go to cities where they are welcomed and feel wanted.

Talk about what you did at Hard Rock Stadium.

With the canopy, it’s the only stadium that is perfectly square. We were trying to do a more futuristic look. We had to span around the spiral ramps. In this case, a challenge became a good thing.

What do you feel or think when you are driving around Miami and you see so many buildings that you and the firm have had a hand in creating?

That? I don’t think about it. I go one at a time. ♦