By Kevin Gale

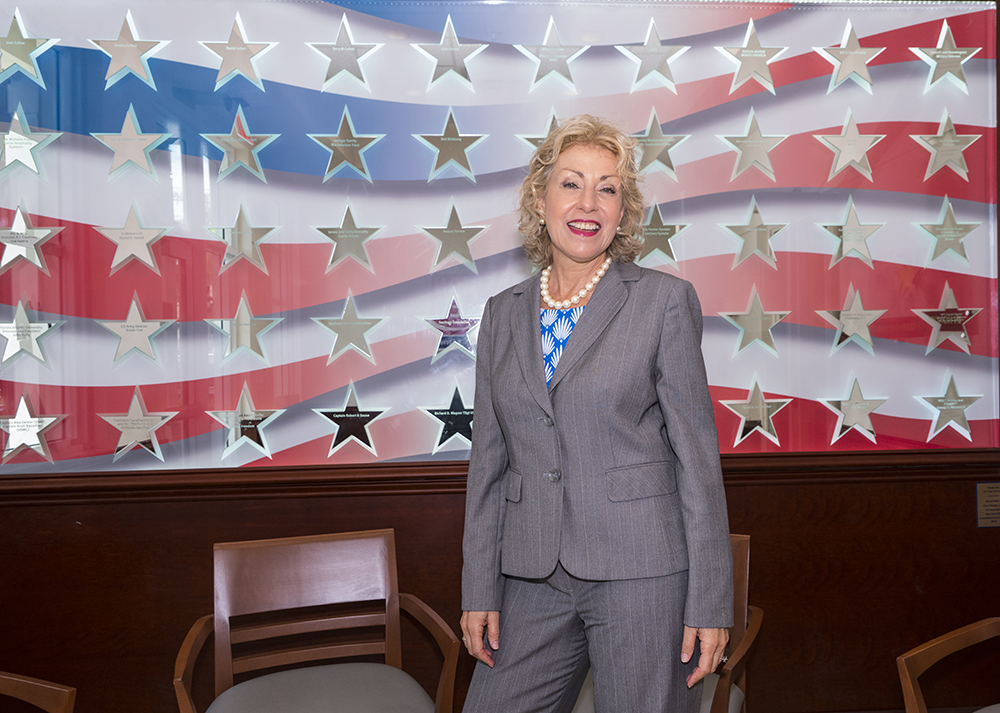

One might grab a line from Monty Python—“and now for something completely different”—to describe veteran banker Lynne Wines’ current career move.

Wines is leading a major push to help the homeless in Broward County as senior director of the Broward Business Council on Homelessness, an initiative backed by the United Way of Broward County, governmental agencies and business groups, including the Broward Workshop and the Greater Fort Lauderdale Alliance.

Wines’ transition comes after serving as president and CEO of First Southern Bank, president and COO of CNL Bank and president and CEO of Colonial Bank, formerly Union Bank of Florida. More recently, she spent a year at Harvard University’s Advanced Leadership Initiative and getting a master’s degree in public administration at New York University.

One key connection to Wines’ previous endeavors was serving as chairwoman of United Way of Broward County, which hired the current United Way president Kathleen Cannon during that time.

Wines and Cannon developed a friendship that resulted in Cannon calling Wines in New York City to tell her about the homeless initiative, saying, “We really need someone with a business background, but someone that also has a heart for the community and nonprofit work,” Wines recalls. “This was months ago, and she just said think about it.”

Wines had planned to teach, but she came down and met with the United Way board, many of whom she already knew.

“I kind of got hooked on the mission. I’m already hooked on the people. They are amazing people,” she says.

Banking Career

In tackling the tough problem of homelessness, it might help that Wines overcame the challenge of being a pioneer in the traditionally male-dominated world of banking.

She started her career as a teller and subsequently became a controller with Union Bank when it was a $25 million asset institution on U.S. Highway 441 in Lauderhill.

“Many, many times, more than not, I was the only woman in the room,” she says. While today there is plenty written about women in leadership roles, there wasn’t much of that back then.

“There wasn’t a lot of help. You had to work really hard. Some people resented it because I was a woman, and you had to keep plowing ahead.”

One advantage, though, was having bank chairman Stuart Miller, who also founded Lennar Corp., as a mentor. Wines found she had a phenomenal opportunity to learn and grow during her 20 years there. For two years, she was the market leader for Colonial Bank after it acquired Union. Then, she became president and COO of CNL Bank. Her role was to grow the bank, but she joined in January 2008, just before the Great Recession tore up the banking industry. Wines left after it became clear that growing the bank wasn’t going to be possible anytime soon.

However, the recession provided an opportunity in 2011: leading First Southern Bank, which was formed from three failed banks.

“I came in first as president and then ultimately became CEO to bring them together and clean them up to create one more valuable organization,” Wines says. She was successful, and First Southern was sold to CenterState Bank in 2014.

Time of Transition

Her husband, along with her mother and best friend, all died in a single year, and Wines decided she didn’t want to keep doing the same thing. Although she became a director at BankUnited in 2015, a position she still holds, she went off to spend a year at Harvard.

“It was a wonderful opportunity and a wonderful experience with people like me from all over the world that were transitioning out of careers … into more nonprofit work, social entrepreneurship and public service,” she says. Wines didn’t so much pursue a specific course of study as she was attending all sorts of classes and lectures that promoted the thinking and attitude of public service.

“I loved it so much that I went on to get a master’s in public service. That was at New York University,” Wines says. Her boyfriend, who is an attorney, was living in New York and it was a city she had always loved.

Wines kept her home in South Florida, though, and says, “So, now I get to go home.”

Wines has been involved with the United Way for 20 years and remembers her first volunteer job was laying sod at a school. With her finance background, she served on the allocation committee that helped direct which nonprofit organizations United Way funds.

Launching the Initiative

One of the first big events for the homeless council was a two-day trip to Orlando to understand how the city has reduced its homeless population by 60 percent. The more than 30 attendees included Castle Group founder James Donnelly, former Broward College president David Armstrong, Transworld Business Advisors CEO Andrew Cagnetta, Broward County commissioner Nan Rich, Florida Blue market president Penny Shaffer, Holy Cross Hospital president and CEO Patrick Taylor, Fort Lauderdale mayor Dean Trantalis and Las Olas Co. president Mike Weymouth.

The key person in the Orlando turnaround was Andrae Bailey, who was then CEO of the Central Florida Commission on Homelessness. He is now an adviser to the effort in Broward County.

One essential step in Orlando was quantifying the cost of homelessness vs. placing someone in permanent supportive housing. Orlando and other cities have found it costs significantly less to have someone in supportive housing, Wines says. The public cost of the homeless is driven up by factors such as emergency room visits and a higher rate of police interactions.

Data is being collected in Broward County, and Wines is confident the cost trend will hold there as well.

As for funding, the council received a big boost in early August when AutoNation announced a $300,000 challenge grant that seeks matching funds from the business community. Donnelly and AutoNation chairman and CEO Mike Jackson are co-chairs of the council.

One of the first priorities of the council will be finding permanent housing for the chronically homeless in downtown Fort Lauderdale, which is symbolized by a tent camp next to the main library.

“Right now, we would like to hear from any landlords in Broward County,” Wines says.

Once the homeless find homes, there will be a collaborative effort to help support them with services. Existing social service agencies and the county are already supporting the effort, but volunteers might also might be needed for things such as delivering food or setting up apartments, Wines says.

She’s realistic about the scope of work ahead. “We want to make progress quickly in the short term, but are we absolutely going to do away with homelessness in Broward County? No. This is a long-term strategy and a long-term initiative,” she says.

Want to help with the initiative? Contact Heather Davidson, the United Way’s director of public policy and advocacy, at hdavidson@unitedwaybroward.org or 954.308.9277. ♦