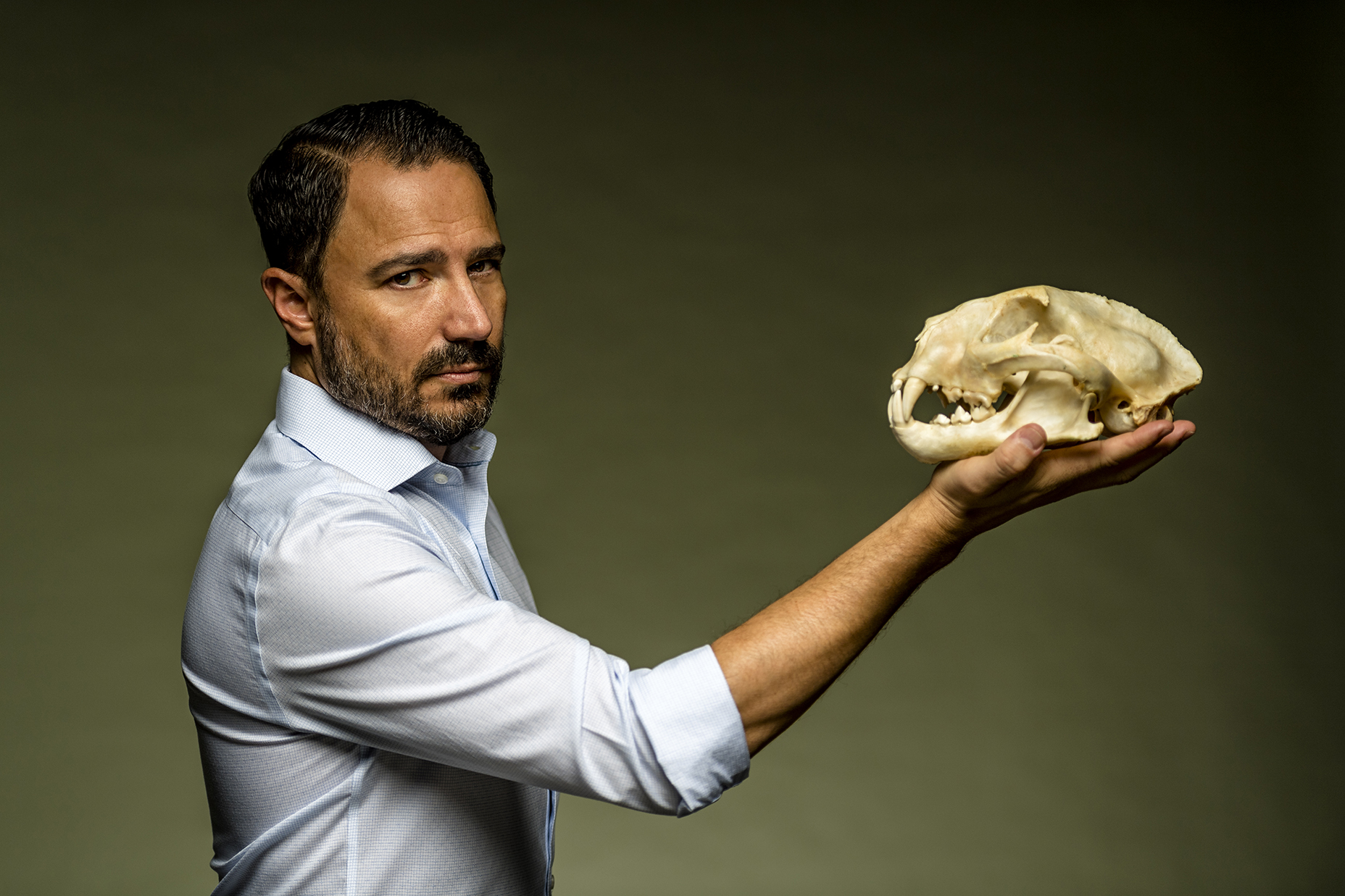

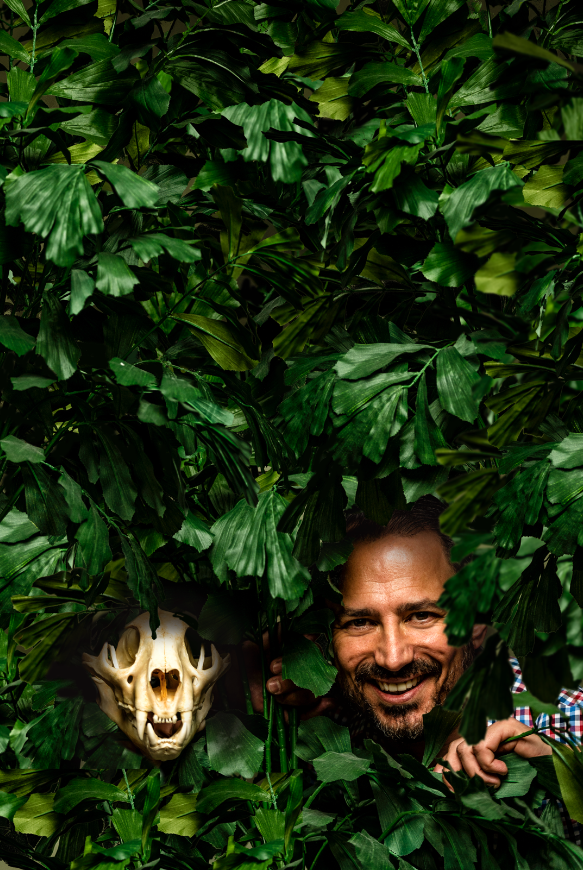

Despite his dapper duds and James Bond accent, Joe Cox is most at home in the natural world—both the literal natural world and the lost past when dinosaurs roamed the earth. The U.K. native has achieved a sterling résumé in his field: four years as senior naturalist—followed by another four as nature center director—at the Conservancy of Southwest Florida; nearly eight years as the founding executive director of the Golisano Children’s Museum of Naples; and more than five years at Massachusetts’ EcoTarium. So when Cox was nabbed by the Museum of Discovery and Science three years ago, he was bound to make a splash as president and CEO. When he enthuses about his role—administrative, educational, strategic—it’s as if he knows each of the more than 450,000 annual visitors by name and interest area, and more than a few extinct, ferocious-looking colleagues.

DINOSAUR AVATAR

We’re not going to begin with the beginning.

OK.

We’re going to start with dinosaurs. What was the first dinosaur you fell for?

Easy. Stegosaurus. Stegosaurus was one of the very first dinosaurs I ever saw at the Natural History Museum in London. And when I moved on to the EcoTarium, they had an incredible stegosaurus there called Siegfried. I have a Siegfried plush toy sitting in my office as we speak, and stegosaurus is a lovely herbivore, with great defensive armor. And it’s just one of those iconic dinosaurs that’s easy to fall in love with.

Is that the type of dinosaur you would choose to be?

Oh, no, if I could be a dinosaur, it would be a velociraptor. Quick, fast, running around, agile, smart. Working in teams, collaborative. There’s something about dinosaurs. You know we have saber-tooth cats and megalodons and mammoths as well. But I think it’s something about the size: Dinosaurs are big to us, but when you’re 5, dinosaurs are huge. Kids just have this excitement about them: the mythicalness and a bit of the coolness of dinosaurs. Of course, dinosaurs have been part of the cultural landscape for so long now. At MODS, we have this incredible movie, Dinosaurs of Antarctica—it’s playing at our museum and will be for a while. One of the paleontologists in the movie talks about how there’s this explosion of paleontologists now because Jurassic Park came out in 1990. A lot of children who watched Jurassic Park went on to become paleontologists.

So let’s go back to when you were a kid. Your accent tells me you’re from the U.K.

Sure, so, I grew up in the U.K., started out life in the U.K., attended a boarding school in England. My parents moved overseas to the island of Malta. My mom’s Maltese and my dad’s British. So, we moved to the island of Malta, and I was always that kid who was, you know, asking questions, wanting to know why the sky was blue or the grass was green, and, who lived in this castle that was a ruin at the end of our street in the little English village where I grew up.

How did they respond to your inquisitiveness?

My parents, very thoughtfully, took me to a lot of museums. The U.K. has an abundance of history, museums and castles, so that was what we would do on the weekend. Our school did an annual trip to London, and the sixth-grade class would go for an entire week, and do absolutely everything. I remember we used to play with marbles in the playground. And our teacher was so excited about this trip to London, and he kept going on about how the highlight would be the British Museum—to see the Elgin Marbles. And I thought, this is incredible—famous marbles in a museum. So we get to London, and we’re going through the Natural History Museum, and I just fell in love with dinosaurs and the dodo bird and it’s just spectacular. And then he takes us to the British Museum to see weapons and artifacts.

Did you ever get to the Elgin Marbles?

With great pomp and circumstance, he announced, “Now we’re going to go see the Elgin Marbles.” And we walked into this giant room and there’s nothing but statues of naked people. And here’s me in sixth grade, looking for that little glass marble in the playground. Suddenly, we had this epiphany that we had no idea what he had been talking about. And that was one of the first times I realized just how impressive museums could be. We studied the Elgin Marbles and we learned everything about them. I fell in love with Roman history and Greek history, and I’ve just always been a museum nerd ever since.

[/vc_column_text][vc_empty_space]

[vc_column_text]

CAREER PATH

CAREER PATH

And then your formal education followed this path?

I was in Malta until I moved back to the U.K. to go to university, did my undergrad. My undergrad degree was in environmental science. And I was in London, so I had access to all of the museums and spent a lot of time focusing on paleo biogeography, which is the study of ecosystems, at the end of the last ice age, essentially. And so we spent a lot of time doing research into what would now be considered paleoclimatology—in a lot of ways, it kind of ties into our Florida fossils exhibit at the museum, and our work on climate change and resiliency.

What was your first job?

I was the development director for the Malta Ornithological Society, which is now called Birdlife Malta—it’s essentially an organization that is the equivalent of the Audubon Society in the U.S. I saw an ad in the paper one day for someone to raise money to support this birding organization. And I had never had a job before or knew anything about fundraising. But I loved birds and was a bit of a birdwatcher. So, I decided I could do that. I was 18, in my gap year, and decided to apply. Unbeknownst to me, I was one of the few people who applied for the job, I suspect—and I got the job. I was tasked with raising the funds to build a nature preserve. So, we raised money and built a nature reserve on the island of Malta. I think one of the great things about that experience for me was really seeing the nonprofit world for the first time. And I was there while the Malta Ornithological Society was transitioning into Birdlife Malta. So, they actually flew me to the U.K. to spend a week at the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds to really learn about how the world of nonprofit fundraising works. Being able to be a part of creating a preserve that is still there today was pretty spectacular.

You had a lightbulb moment about Florida, didn’t you?

I finished my undergrad wanting to put off working as long as possible. I was talking to my biology professor one day, and just not really sure what I was going to do next. And he had a poster in his office of this guy, sitting on a classroom floor, holding a snake, talking to a group of children. But in the poster, what caught my eye was outside the window—blue sky and palm trees. It was a promotion for an intern position that he had set up. And so, six weeks later, I was on a plane flying to Miami to start my job as an intern at the Conservancy of Southwest Florida in Naples. I’d never been to the States before, and could barely tell you the difference between a mangrove and a manatee, but here I was about to spend nine months being an education intern right here in South Florida.

What was eye-opening about the experience?

I’d had a taste of the nonprofit world and fundraising, but hadn’t really seen the education side in great detail, and nothing compares to that incredible moment when a child has an experience for the first time, whether it’s looking through a microscope, having a face-to-face encounter with a life-sized megalodon, or soaring into outer space in an IMAX Theater. And I fell in love with museum education.

[/vc_column_text]

[vc_empty_space][blockquote text=”I think, as the CEO of a museum, the most crucial relationship that you have is with your board chair and with the board leadership.” show_quote_icon=”yes”][vc_empty_space][vc_column_text]

VALUES-BASED

Tell me about the chain of command and relationships at the Museum of Discovery & Science.

I think, as the CEO of a museum, the most critical relationship that you have is with your board chair and with the board leadership. That’s always something that I’ve looked at very closely. Building that relationship is a key part in building a culture of inclusivity within an organization.

Let’s hear more about that collaborative environment.

We’ve spent the last two years working on our strategic planning process. And that was very much an inclusive process involving our entire staff, volunteers, our interns, community partners, visitors—really trying to build a vision forward that is a shared vision for the museum. It’s also about responding to the needs of the community and building it up, from board and staff to partners and donors. That’s always been my approach—not necessarily me coming in and saying, “Here’s my 10 things that I’m going to do.” It’s really listening to the needs of the community and finding out what the values of the institution are and bringing those to the forefront, so we were very excited to launch our 2020-2025 strategic plan.

How do the museum’s values inform programming?

We have four key pillars: early childhood education, environmental sustainability, health and wellness, and physical science. And so those are the areas where we really focus. We created the Wise Bodies program, which was a physical program going out into schools and delivering an assembly-style program where we talk about awareness and prevention of HIV and AIDS. We worked with the AIDS Healthcare Foundation and Broward County Public Schools, and we just launched a brand-new virtual version of the curriculum. Eventually, we’ll have 12 videos that are designed in a way so teachers can use them very easily; they’re addressing everything from health and wellness to STEM—science, technology, engineering and math. And we’re engaging students in a way that encourages debate and also encourages arts appreciation and art creation.

How did you deal with the pandemic?

We were incredibly fortunate to have a board member who said, “Let’s get into some virtual content.” And so, we kicked off immediately with developing what we call our Virtual Camp Discovery. On March 16, our doors closed, but the museum remained very much open, virtually, with videos addressing STEM education to hurricane awareness to making stomp rockets or exploring your Florida backyard—with more than 900,000 views and counting!

What pandemic accommodations is MODS making now?

We’ve diligently prepared for the safe return of our community. Visitors to the museum can expect a safe and socially distant day of fun to explore our 150,000-square-foot science center AutoNation IMAX theater and outdoor Science Park. With less than half of children in Broward physically in school, a visit to MODS is a unique way for families to extend STEM learning opportunities and help limit the impact of the “COVID slide”—the educational learning drop off that many children are experiencing in Broward County and around the country.

Photos by Nick Garcia