A moment of truth emerged pretty rapidly during my visit to the McCawley Center for Laser Periodontics and Implants. Dr. Tom McCawley had taken a sample of my breath with a pipette and put it in an OralChroma testing device that was hooked up to a laptop. After finishing a tour of the office, we came back to look at a bar chart that showed three different type of gases that cause bad breath. The machine measures parts per billion.

There’s hydrogen sulfide (rotten egg smell), methyl mercaptan (feces) and dimethyl sulfide (rotten cabbage). Fortunately, mine weren’t too bad, probably because I had been to Dr. McCawley before for an implant and his brother, Daniel, has been my dentist for decades.

I’ve learned good practices like using a tongue scraper. Mark gave me a new metal one that was bent into the perfect shape to reach way back into my mouth. You want to go so far that you almost want to feel like you are gagging and then scrape 20 times. (Hey, nobody said having good teeth and keeping bad breath at bay is easy.)

Tom explained that the tongue is a deeply layered organ like a shag rug, so it takes a bit of work to keep it clean. Basically, you scrape enough regularly so your tongue looks pink instead of having a white film on it.

If you don’t do that, the McCawleys come to the rescue with a patented ultrasonic instrument that vibrates bacteria out all the way from the base of the tongue. Tom said they are one of only two places in the United States to treat bad breath the way they do.

During my visit, Mark took some scrapings from my mouth, so it could be examined under a higher-powered microscope that can be projected onto a video screen in an exam room.

While the amount of wiggling bacteria in my mouth seemed like something out of a horror movie, Tom reassured me that my mouth wasn’t so bad at all. The McCawleys are highly trained to recognize various types of bacteria. Tom said they are one of only two places in the United States to treat bad breath the way they do.

The McCawleys also offer an option in treating infections around implants, which are more subject to that than natural teeth.

Typically, other dentists don’t know what to do, so they take the implant out, Mark says. “That’s traumatic to the patient,” he says. Unfortunately, some of those implants can’t be replaced because of issues like bone loss.

“We have been able to pioneer how to disinfect and how to rebuild the bone around the implant,” Mark says.

The practice has many patients who travel internationally to get treatment. Fortunately, for suffering South Floridians, it’s an easy drive to the Cumberland Building at 800 E. Broward Blvd., where patients get a bird’s eye view to the north from the McCawleys’ seventh-floor offices.

No research? Let’s do our own

The senior McCawley has a history of innovation, often funded with his own money. He spends just a few days a week in the office these days, but works full time to give lectures, conduct research and co-publish PerioDontal Letter, which is sent out three times a year to 15,000 dentists and periodontists.

Some of Tom’s initial research was born out of frustration. The traditional treatment for bad gums was to cut away the tissue.

“It was treating the results of the disease and not the cause,” he says. He heard about a laser system approved in Canada and went to Windsor to check it out. He thought it would work to get rid of the bacteria.

“When it first came out, people claimed there was no research and guess what—they were right,” Tom says. He partnered with a university to do a study and proved his supposition.

There was a dearth of information on bad breath, so he did a study on that, too. The pre- and post-treatment measurements of bad breath odors proved that it worked.

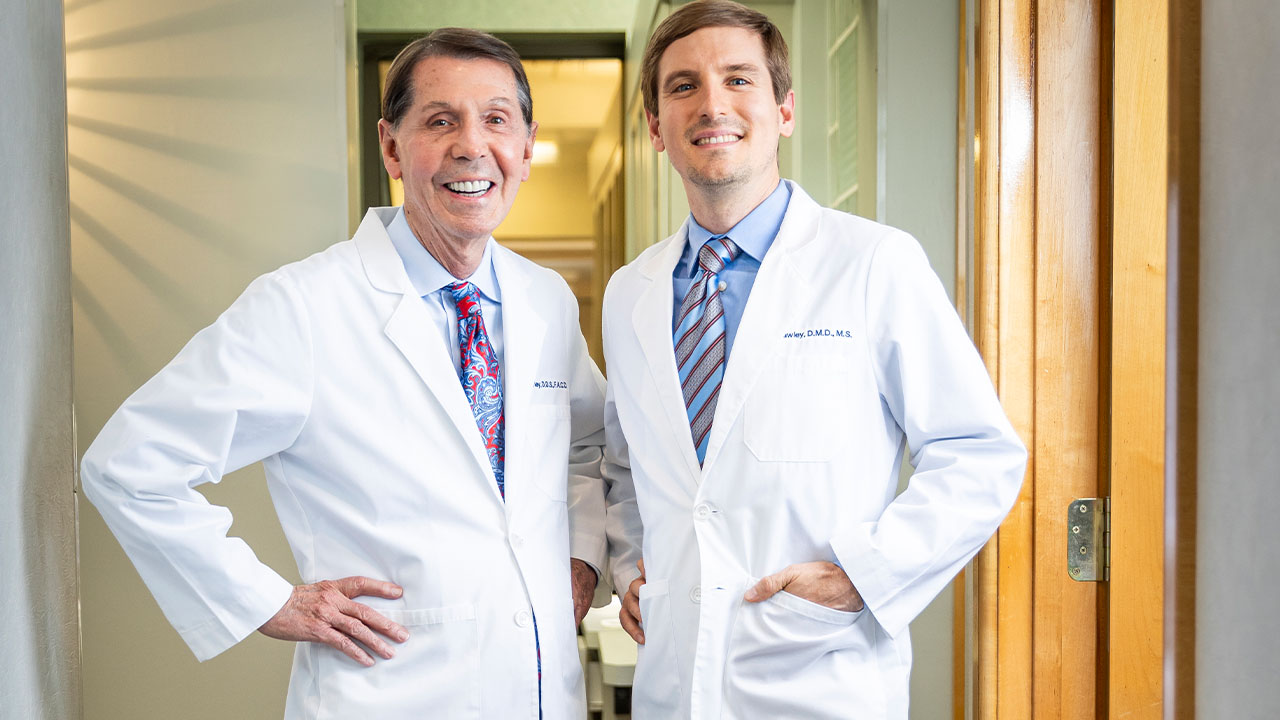

An early start for Mark

Mark says he started helping out around the office when he was five.

“I think when he was 7 years old he did a little drawing—I want to be a periodontist like my dad,” Thomas says.

“I made my career decision very young and stuck with it,” Mark says.

Did he have trepidation about joining his father’s practices? Mark says he knew what to expect, but it might not have gone so well with some of his other brothers, who butted heads with their dad. (Maybe it was an earlier indication of skills that led them to be lawyers.)

“It worked out better than we could have hoped. I am able to buckle down and be the workhorse here and he’s kind of able to do some of the ancillary things that still need to be done,” Mark says.