Whether due to tax reasons, general lifestyle considerations, or COVID-19 (and the suddenly ominous density of Manhattan), some of the biggest names in the financial world are joining the migration to South Florida. First Carl Icahn, then Goldman Sachs. And Jamie Dimon, CEO of JPMorgan Chase, is once again flirting with a move to Miami—both for himself and his headquarters. In the past, some of JPMorgan’s executives resisted, nervous about what they perceived as the substandard quality of the schools in the state.

Dimon doesn’t have to worry about his own kids on that score: His three children, all daughters, are already out of college. Two went to Duke, and the third is a Barnard graduate; for his part, Dimon holds a B.A. from Tufts, summa cum laude, and an M.B.A. from Harvard.

But there were likely concerns about recruitment and the quality of the state’s talent pool. According to the U.S. Census, the percentage of B.A. degree-holders in Florida is around 28.5 percent, compared to 32.6 percent in California and 35.3 percent in New York state. And nearly 50 percent more people in New York (15.4 percent) have advanced degrees than in Florida (10.3 percent).

But whether Dimon pulls the trigger in 2021, or later, or never, the influx from the Northeast—and less expectedly, from California—continues, heating up the residential real estate market throughout South Florida and positioning the region as the financial and tech powerhouse it has long aspired to be. It is inevitable, however, that as businesses, their employees and their families migrate south, questions about the state’s educational profile will nag.

The eight-member Ivy League, to cite one indicator, exists within a geographically tight Northeast radius containing New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Connecticut, Rhode Island and New York (which 130 colleges call home, the most of any state). And that’s not even counting the Ivy-comparable M.I.T. Meanwhile, the state of California contains numerous schools on the same exalted level.

The eight-member Ivy League, to cite one indicator, exists within a geographically tight Northeast radius containing New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Connecticut, Rhode Island and New York (which 130 colleges call home, the most of any state). And that’s not even counting the Ivy-comparable M.I.T. Meanwhile, the state of California contains numerous schools on the same exalted level.

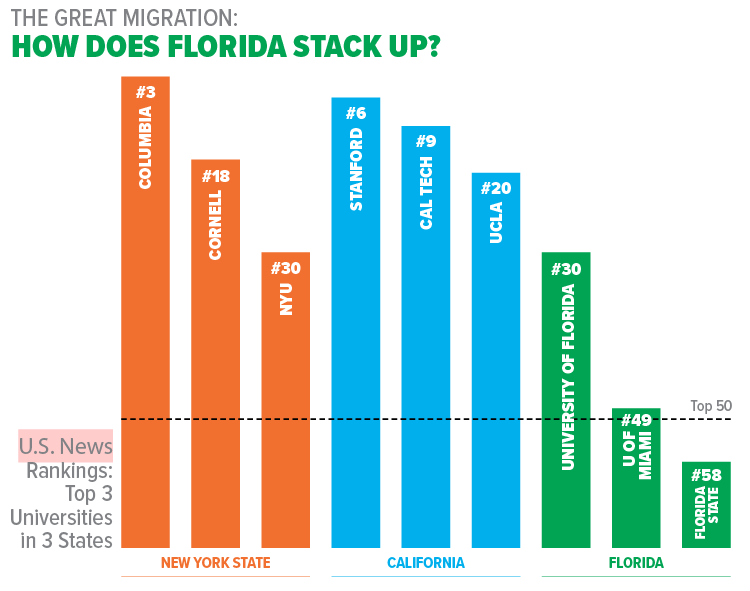

It’s going to take some doing for Florida to catch up. If we look at the U.S. News and World Report rankings and apply an admittedly reductive comparison of just three states—New York, California and Florida—the numbers are revealing. New York State boasts three institutions in the top 30, starting with Columbia University sitting at #3, with Cornell and New York University also in the mix. The Golden State, meanwhile, has three schools within the top 20 and six within the top 30, with Stanford at six and the state’s stellar university system accounting for no less than three top 30 slots (UCLA, UC Berkeley and UC Santa Barbara).

Meanwhile, Florida’s top-ranked universities find themselves in the top 100 but lower on the list: University of Florida (30th) and University of Miami (49th). Of course, many students opt for an out-of-state education, but a good number stay close to home for reasons that range from convenience to family support to cost. And having highly ranked schools within your home state’s borders feeds an information-based economy; a thriving creative class; and a generalized, location-based sense of prestige and achievement.

So it would appear that the state of Florida has itself a mission: to boost the rankings of its schools in order to cultivate and retain top talent in the state over the coming decades. Alex Argudin, CEO of the Miami Parking Authority, sits on the president’s council of her alma mater, Florida International University in Miami. “I am keenly aware of student migration to and from Florida,” she says. “This trend presents challenges, but also opportunities. The Next Horizon campaign is attracting investments that are expected to continue to increase the University’s ranking.” Next Horizon’s fundraising has been robust by any standard: The initiative has notched more than $600 million of a $750 million goal.

What Argudin hits on is unsurprising: The way to increase a school’s stock is money. Money to build better student facilities helps, but the best investments are in developing research centers and luring world-class faculty. To be sure, not every parent, student or employer cares about rankings, but if you do, it helps to think about a university’s ranking the way you think about investing in a stock—you want to catch it when it’s on the rise.