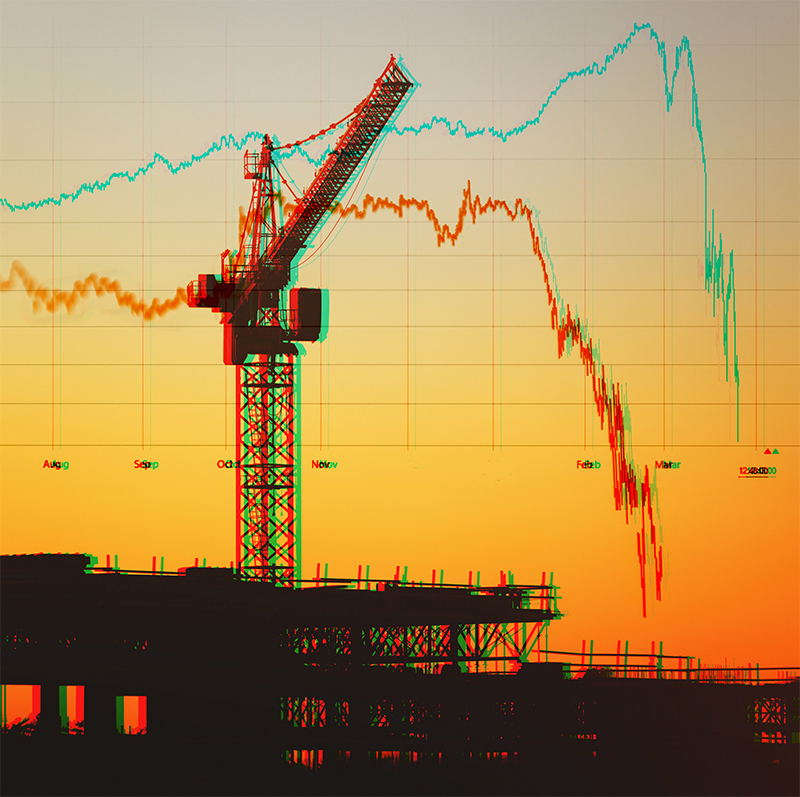

Most South Florida office developers will tell you there’s mounting demand and market fundamentals to support new office construction in many pockets of South Florida.

The problem is that lenders and institutional investors won’t bankroll new office buildings without pre-leasing. And, since it is unbelievably hard to get a company to lease something that doesn’t exist, new office projects have remained largely absent in the current real estate boom.

But, South Florida office developer Rodrigo Azpurua is bucking the trend.

Azpurua, CEO of Miami-based Riviera Point Development Group, is delivering two new speculative office mid-rise buildings at Florida’s Turnpike and University Drive in Miramar; breaking ground on a third, 41,000-square-foot office condo building in Doral; and planning a fourth, 72,000-square-foot office building at Southwest 145th Avenue and Southwest 27th Street in Miramar.

And yes, Azpurua is still using “other people’s money” to do them all.

Instead of making capital-chasing calls to banks, pension funds and other Wall Street institutions, Azpurua is courting investors in China, Venezuela, Argentina, Columbia and even Russia to fund his South Florida office developments.

Azpurua is among a burgeoning number of developers harnessing foreign investment capital tied to immigration visas, rather than relying on conventional sources, to finance real estate projects.

It’s a complex process, often cumbersomely bureaucratic, and not for those lacking patience or the willingness to reprioritize project objectives.

The program, called EB-5, awards green cards to foreigner investors and their immediate family members for investing $500,000 in projects or business enterprises that create at least 10 jobs in a targeted employment area.

Administered through the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, EB-5 visas are conditional until the jobs are delivered. Developers have 24 months to generate the required jobs. If they fail, the investor and their family members lose their conditional visas and are sent packing.

It’s not a new program, but is rapidly gaining popularity.

Last year, for the first time in the program’s 25-year history, the maximum ceiling of 10,667 visas was hit, generating about $2 billion in immigrant investment capital for U.S. projects.

�Everything has changed over time,” says Ronald Fieldstone, a lawyer specializing in EB-5 at the firm of Arnstein & Lehr in Miami. “EB-5 was kind of insignificant until 2009. Nobody really focused on it.”

Then the Great Recession hit, zapping capital and financing.

“You can see that in the last five to six years the program has expanded and become mainstream,” Fieldstone says. “Real estate developers, in particular, have looked at EB-5 as a source of capital.”

EB-5 investors essentially loan money to developers at relatively low interest rates. Much of the interest generated by the money, however, goes to the offshore marketing agents that pair immigrant investors with development deals.

Investors are more focused on getting green cards than profits, Fieldstone says. Developers later repay the investors by refinancing the project or selling it.

Fieldstone says the success rate is “very high,” estimating that 90 percent of the conditional visas issued become permanent.

To develop the newly completed 63,000-square-foot Professional Center at Riviera Point campus along Florida’s Turnpike at University Drive in Miramar, Azpurua raised $17 million from 34 EB-5 investors. About half were from China.

“If you are used to doing the traditional income property model, then forget about,” Azpurua says. “My main goal is to create the jobs and satisfy my EB-5 clients.”

The first 29,000-square-foot building opened in June and the second 34,000-square-foot building is slated to open this spring. To meet the job requirement, Azpurua needed to create at least 340 jobs, which can include longer-term construction jobs, property management and tenant-generated jobs. He has done that. But, he had to make investor visa status, not top rent, his first priority.

Azpurua needed to hit 85 percent occupancy at the first Riviera Point building to get over the job creation threshold, so he aggressively began offering below-market deals and short-term leases to fill the building up fast.

“It is not compatible with traditional ways of looking at real estate,” Azpurua says of the program’s job creation burden. But now that he has satisfied the job requirement, he can focus on getting market rent at the second Riviera Point building. He plans to sell both buildings as fully leased and stabilized income-producing assets.

“I never thought it was going to be so personal,” he says of his EB-5 client relationships. “I never thought it would take so long, and I never thought I was going to need such long-term vision.” ?

Freelance writer Darcie Lunsford is a former real estate editor of the South Florida Business Journal. She is the Senior VP for leasing at Butters Group and is avoiding a conflict of interest in her column by not covering her own deals.