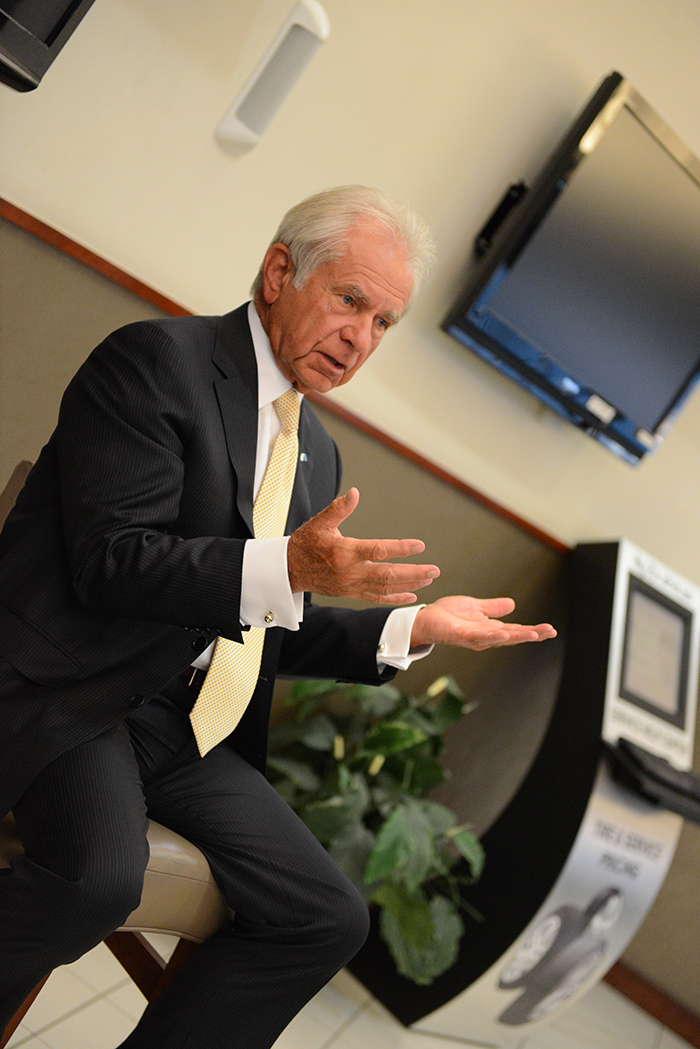

John Kanas burst onto the business scene in South Florida as part of an investment team that took over the remnants of BankUnited after it was seized by regulators during the Great Recession.

Kanas has a long history in banking, though. During our CEO Connect interview he tells how he became the youngest CEO of a bank. He spent three decades growing North Fork Bank into a New York powerhouse that was eventually sold to Capital One.

Here are edited highlights from the interview that was conducted live before an audience at JM Family Lexus by Gary Press, the CEO of Lifestyle Media Group and SFBW magazine.

Your bio says it’s believed that you were the youngest bank CEO in America in 1977 at the age of 29 at North Fork Bancorporation. How did that happen?

I was the only one with the combination to the safe! Actually, I started there as a kid when I was 24 years old. It was a small company, a $240 million bank, I thought I would work there a year or two and go to law school.

The guy that ran the company got sick and was not able to run it. The board asked me to run the bank on an interim basis while they looked. I was interim for a month, then six months, then after a year we got a letter from the New York State regulators that we had to have a president. I became permanent.

I planned to stay 18 months and ended up staying there 35 years.

An article on BankDirector.com says you turned Wilbur Ross down when he asked you for a loan in the 1980s. How did you go on to establish a relationship with him and eventually form a group to acquire BankUnited?

Wilbur and a bunch of other rich people belonged to the South Hampton Beach Club and they wanted to buy it. They came to us to borrow the money. Wilbur came to me via Muriel Siebert, who was the first woman on the New York Stock Exchange board to own her own company. She was a partner in the beach club with Wilbur Ross and a long-time friend. They said none of them wanted to guarantee the loan. I said, “You don’t want to guarantee the loan, but you want me to guarantee the loan?” Wilbur said Chase Manhattan would do it. Six months later they came back. Chase Manhattan wouldn’t do it.

After I left North Fork, Wilbur was managing an equity fund with $4 billion. He was an expert in distressed business and I knew about banking. We scoured the country looking at over a 100 opportunities and found BankUnited. Wilbur put up $240 million and was followed by the Blackstone and Carlyle Group.

You did at least 17 acquisitions at North Fork, but you have been more reserved at BankUnited. How does a CEO know when it’s the right time to do an acquisition?

It’s not for not trying. We expected to acquire a dozen or more banks after we came to Florida. After we bought BankUnited – it was very creative and lucrative – Goldman within six weeks raised $25 billion for people to come to Florida and do the same thing we did. So the economics of the deals never made sense. We have talked to 50 or 60 banks in Florida, but have never agreed on price.

We think banks should trade at a lower multiple than banks are willing to sell them. The stocks are coming down and we think we might make a deal in the next year either in Florida or the northeast.

CEOs often face a tough choice of when to sell. How do you know when it’s the right time to sell?

You’re basically a fiduciary responsible for other people’s money. The last acquisition we made at Capital One was Greenpoint, a very large mortgage lender. Through the prism of Greenpoint we got to see the problems of the residential mortgage market before others did. We were surprised the Fed didn’t see it.

We quietly talked to some people in 2005 that had always expressed an interest in North Fork and that led to the transaction in 2006. North Fork on its own would have been hard pressed to withstand what was coming.

We see no such issues today in Florida or New York. I think we happen to be in the two strongest markets in the country. We know real estate values will peak in Florida and decline again. We think it’s years away though. We don’t see the type of leverage we saw in 2006. We think we are still building value. When we see that the value will increase, we don’t think about selling the company. We think the best days are ahead of us.

What did you see when your investment group made a successful bid for the failed BankUnited that other investors didn’t see?

We were searching for the biggest disaster we could find. We knew BankUnited would be an effective bankruptcy and the FDIC would have to back the deal. The world was falling apart – you had Lehman and Bear Stearns imploding. It was very hard to raise money.

The FDIC sent out 63 bid packages for BankUnited, but they only got three responses. Our biggest worry was that the FDIC would fail – that the federal government wouldn’t backstop it. We knew financially if we worked the FDIC pricing out over 10 years that there would be a big return. We didn’t know we could build a company that would be strategically important.

The $900 million in capitalization has grown to $3.5 billion in market capitalization. We took a risk that others were unwilling to take. Some investors turned me down. They thought things were so bad that the entire banking system would be nationalized.

Do you enjoy pushing the edge, such as the BankUnited ads that featured competitor BS Bank?

We purposely want to push things. I learned a long time ago in this business that bank advertising is boring. We all say, “We have the best rates in town. We are friendly and accommodating.” We have all been partially wrong.

It always has been my opinion that you first need to get people’s attention. I remember sitting around with Mary Harris (Senior VP of Marketing) and the advertising crew. They were saying, “What are you trying to say?” And I said that everybody is dealing with all this BS. I was hesitant about the term BS, so we came up with “bank speak.” So we told people who were offended by it, “No, it stands for bank speak.”

You brought Tom Cornish on board. He was previously a top banker in South Florida before becoming CEO and President at Seitlin Insurance. Tell us how Tom fits with your strategy.

During the first month I was in Florida, Tom came to a lunch. We hit it off personally. He helped us get our management team together. We have stayed in touch over the last five years. Tom made a great success in the insurance business. Then, he moved on to sell the company to Marsh. Half of our employees used to work for him at Brand X. I said he ought to come to work with us. He has made huge contributions. He is a very practical thinker and is respected in the business.

Audience question: Tell us about the difference in banking between 1995 and 2014.

The biggest difference is the regulatory influence. Washington really got burned on this recession. Remember Treasury Secretary Hank Paulson had to beg Congress for an $800 billion bailout of the large banks? The small banks didn’t get anything. So, there is an open sore in Washington about the banking industry.

The result is the Dodd-Frank bill. Some people say it’s sort of a nationalization of the banking industry. The regulations are voluminous. The banking regulators are a lot more active and intrusive. You as customers feel it’s because we need a lot more information from you. However, if it works over time, the banking industry should be safer and less volatile.

The biggest difference has been branch banking. The industry has been building branches on every lot they could find. Activity is down 90 percent in some branches.

Everything is electronic – people being paid electronically from the government and their employer. It has made the business much more efficient. As the younger generation comes along, they get more comfortable with taking a picture of their check to deposit it and then throwing it away and going to Starbucks. I’d be guessing, but I’d say that over the next 10 years, 40 percent of the bank branches in the United States will be closing.

Audience question: After Florida and New York, where would you be expanding?

I can’t think of two better markets in the country. When I say New York, I mean that 50-mile circle around New York City. In the borough of Manhattan alone, there are $1 trillion in bank deposits and we have $1 billion – so there is a lot of runway. We would rather have a small piece of a very large market. I don’t expect us to stray away from these two markets. ?